Culture Shift

A discarded bra. A stiletto heel missing its partner. A waist-shrinking corset. Items that hold no meaning in a boudoir, but cast them in steel in sizes befitting a storybook giantess, place them out in the open, and those things gain immense power. Power to make the passer-by stop and think, of course. But also power to challenge the status quo. These are the works of Greek-born artist Kalliopi Lemos, whose trio of sculptures are bound to spark questions and debate at their new home on the Peninsula.

In a world where gender pay gaps, sexual harassment and the role of women is in the limelight, Lemos’ work will no doubt be seen as a reaction to the current women’s movement and the frustration felt by those at its heart. But these pieces aren’t just a sign of the times; they’re a type of artistic expression that can trigger change of perspectives and make things happen.

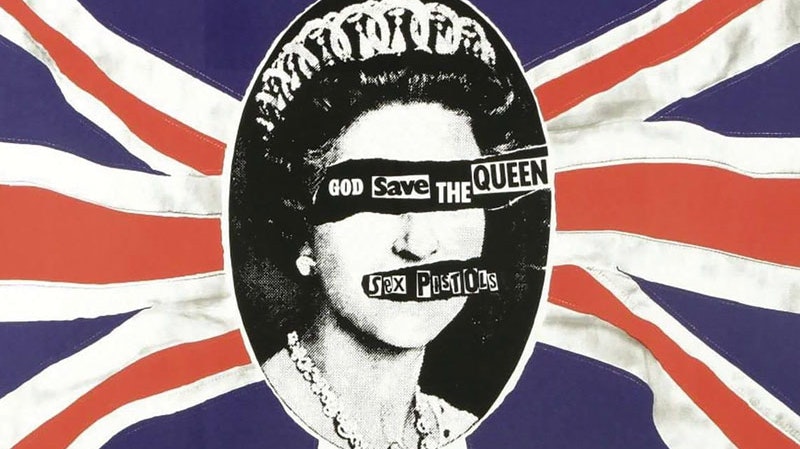

Take 1970s Britain; unemployed teenagers needed a new spokesperson to replace the peace-loving hippy of the previous decade. Obligingly, the Sex Pistols played a 13-song set to a Manchester audience of 40. Not exactly the hysterical mass of schoolgirls packing stadiums with hopes of marrying Paul, John, George or the other one, but that was precisely the point. The existence of super-groups and a music industry that spent millions marketing them joined economic depression and the threat of nuclear war on the list of things to be pissed off about. And in the backrooms of pubs and clubs around the country, frontmen and women with tattooed skulls expressed this growing fury.

“God save the queen/The fascist regime/They made you a moron/A potential H bomb/God save the queen/She’s not a human being/and there’s no future/And England’s dreaming,” snarled Johnny Rotten in the 1977 single that lashed out at the establishment. You know you’ve hit a nerve with Westminster when a Conservative politician hails your music, “disgusting, degrading, ghastly, sleazy, prurient, voyeuristic and nauseating.” Not a fan, then, Bernard Partridge MP? But for the youthful masses, punk was a channel through which to express dissent against colonialism, racism, capitalism, sexism— virtually every ism you can think of.

Punk gave us the guitar riff, the indie record label, and inspired everyone from the unemployed teenager to rising fashion icon Vivienne Westwood. “I was messianic about punk, seeing if one could put a spoke in the system,” said Westwood, whose penchant for safety pins, bicycle chains and dog collars was inspired by political bands who in turn were inspired by her.

And the legacy of punk lives on. It continues to be synonymous with the outcast, the rebel, the man and woman on the street rising up. It’s precisely that spirit which lives on in national and global events, from the women’s marches to Catalan independence, from Brexit to members of the public getting argumentative with brands and politicians alike on Twitter.

“Punk gave us the guitar riff and inspired everyone from the unemployed teenager to the man on the street”

So it’s unsurprising that in 1992, in a nod to her previous life, the Queen of Punk Westwood would collect her OBE and meet the Queen of England knickerless, apparently giving Lizzie a good giggle in the process.

Fast-forward to 1993 and society is once more in the grip of a collective anxiety. The previous decade had seen the rise of a deadly epidemic AIDs and with it intense fear, stigma and misunderstanding. People living with HIV, and by extension homosexual men, were made into pariahs—a survey at the time found that over half of Americans felt infected individuals should be put into quarantine and 15% thought they should be tattooed so they’d be easy to spot.

Then along came Jonathan Demme’s movie Philadelphia in which a dying lawyer fought against his dismissal due to carrying the infection. This depiction of a dying gay man would see enormous strides to dampen social stigma and the portrayal of gay men and women in society. An HIV-positive extra from the film told how a colleague moved her desk back next to hers after watching the film. A tiny, everyday triumph for one individual; a sentiment that would be replicated countless times the world over.

With mistrust of the establishment came angstsy youth punk, with homophobia came film and other creative outputs to fight back. With race relations, Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird pulled no punches in its depiction of 1930s American South and on its 1960s publication it helped throw a spotlight on the civil rights revolution. Warhol’s soup cans were inspired by the permeation of pop culture in western society and BBCs Planet Earth II was more than just a gift to the viewing public in 2016; it was a reaction to environmentalism that has since seen a wave of anti-plastic campaigning by governments and Facebookers alike.

“The bra is an intimate and delicate bit of clothing that women wear. It’s almost non-existent, but it’s something armour-like that guards a sensitive part of their body. Re-imagining the bra as something huge and steel is an extension of the feeling that women need protection.”

What then of Lemos’ 2018 pieces? Her sculptures might be deliberately ambiguous, but the context in which the pieces exist is anything but. Fourth wave feminism is reaching a tipping point, inspiring a growing body of work, from Manjit Thapp’s The Little Book of Feminists to feminist slogans dominating headline fashion shows in recent years. How will this mood influence the casual stroller’s perception of a giant steel corset on a pavement? As a symbol of female strength defiantly declaring “#metoo” or as armour in a patriarchal world?

As public breastfeeding, female pin-ups and women as objects continue to divide opinion, what should we make of Lemos’ discarded lingerie? Is the owner a sexually-liberated woman, declaring herself free of society’s constraints dictating what it is to be desirable, or is she one who has forgotten the sacrifice of her bra-burning forbearers?

These are the questions the Peninsula passer-by may muse over, but Kalliopi can shed some light: “The stiletto heel is a very elegant shoe but this one has a blade as a heel, so it looks attractive but it’s also dangerous. It suggests that some women [in society] feel the need to show that they’re capable as mothers and workers by being elegant and attractive; but it also shows they have the power to hurt if they have to.”

She adds: “The bra is an intimate and delicate bit of clothing that women wear. It’s almost non-existent, but it’s something armour-like that guards a sensitive part of their body. Re-imagining the bra as something huge and steel is an extension of the feeling that women need protection.”

And the corset, “makes the body of the woman elegant and slim, but beyond the elegance and the beauty, it’s about the pain women need to sustain in order to make their way in modern life.”

Kalliopi finds bringing art to life: “exciting because every step of the way, there are challenges and choices to be made.” Just like punk’s raging followers and Demme’s cinema-goers, Kalliopi’s by-standers may find something to say or perhaps something to stand up for.