A Nostalgic Future

We all know that Rome wasn’t built in a day. The well-used motto reminds us that cities and homes take time to create. They move at a glacial pace in comparison to the human imagination, where we can think lightyears ahead.

As technology is gathering speed, pipedreams are now becoming real, and what is new today, will be old tomorrow. But while our imaginings carve out an unfamiliar place, we seek comfort in the nostalgic.

Take the vinyl. We scrambled for Walkmans, then CDs and Mp3s, but we’re now back to record. Vinyl revival is a ‘thing’ with sales booming and surpassing downloads. In a digital age is it the need for tactility, or simply comfort in the old? Either way nostalgia is a trend in tech, with Nokia recently releasing the 90s classic 3310, snake included.

Because when we look at the future, it can be easy to feel intimidated by the unknown, but it also allows us to imagine freely. Science fiction has had a huge influence, showing us fantastical worlds and unthinkable technology. Look at Jules Verne’s 1870 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, which was key in inspiring the creation of the Argonaut submarine.

Or the first rocket in 1926 after its creator read H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds. It doesn’t stop at literature. Film and TV have also become major influences in both technology and design – a British inventor recently flew around in a jet suit around at a TED talk like Iron Man, proving that science fiction has always been a visual template for the future, often guiding new and innovative design concepts.

While some sci-fi looks deep into an unbelievable future – think Star Trek roaming across galactic space – there are also those that sit in the not-so-distant future, uncomfortably closer to home. Black Mirror looks at the possibility of AI personal assistants going beyond home automation and replacing relationships.

“When we look at the future, it can be easy to feel intimidated by the unknown.”

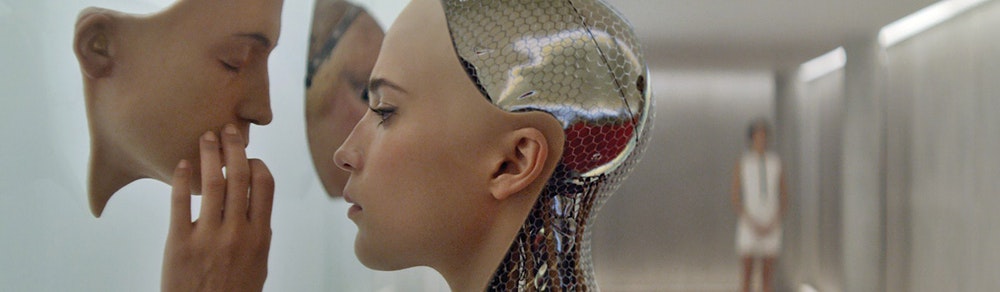

It reminds us of the fears we have about the future of technology – in the film Ex Machina, the AI Ava is given a relatable human face. But why does the unusual give us such chills? When we recognize that something is so similar to ourselves yet that little bit unreal, we recoil. Think dolls, robots and zombies. This is the effect of the ‘uncanny valley’.

Something that mimics reality, yet we know isn’t real, makes us suspicious. It’s theorised it’s because we see robots as a threat, we think that perhaps one day they’ll take over the world.

But we’re at the point now where robots are able to recognize human emotion and the recently released app Replika is marketed as “an AI friend that’s always there for you”. The more you chat with it the more it learns, while it asks you how your day is going, tells you jokes and probes you about your desires. Its sole purpose is to become a friend and users are becoming connected.

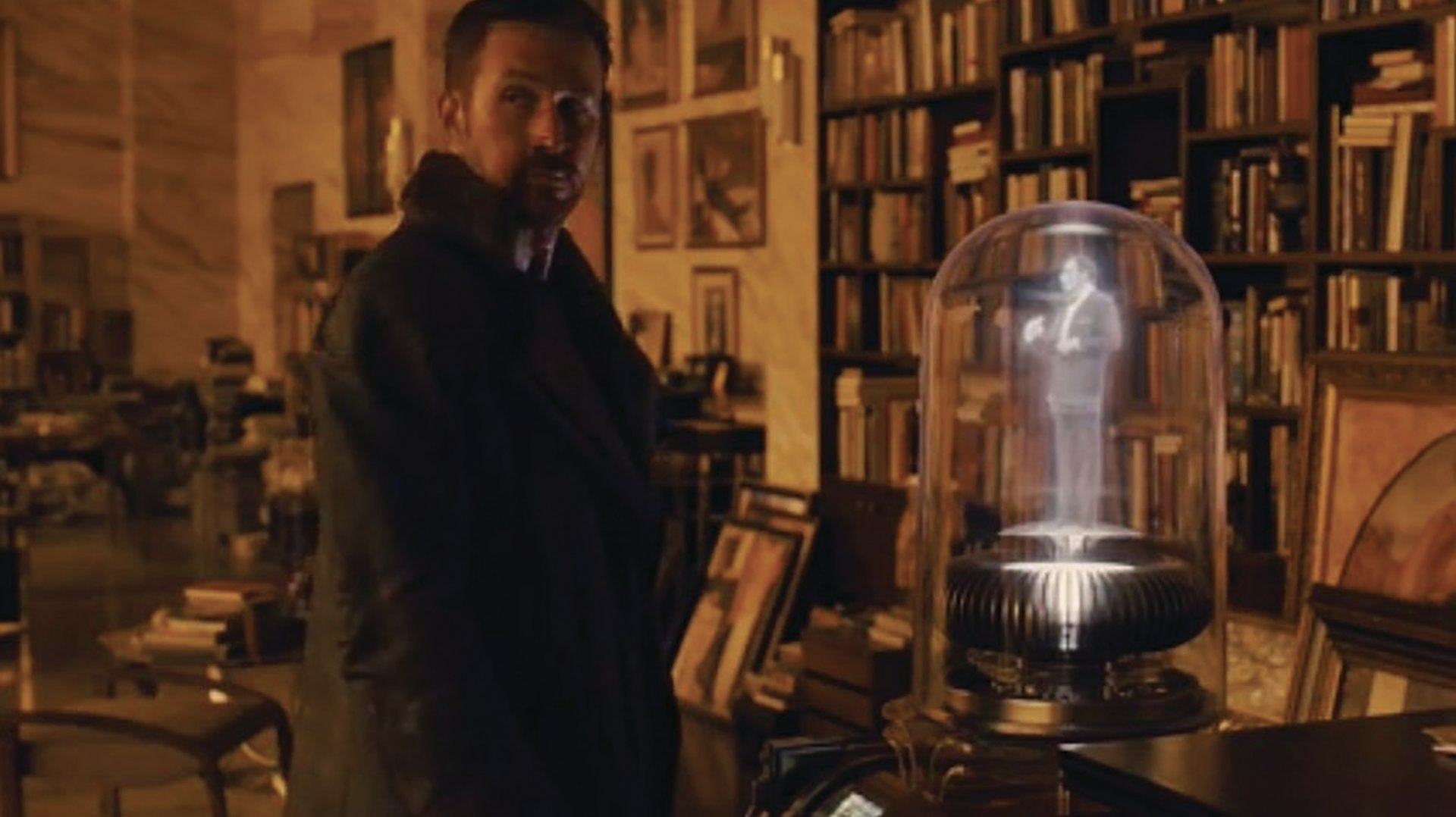

In Blade Runner, 2049 the protagonist, Agent K, is given a hologram for a girlfriend, and she delivers the role of friend, confidant and partner. But she can’t substitute the human touch. Studies show that babies show biological benefits from skin-to-skin contact with their parents, and in Bowlby’s controversial study, the young monkey prefers the comfort of a cloth ‘mother’ rather than the wire ‘mother’, even though it’s the one holding food.

In these instances, humanity isn’t a preference but a must. But who knows if one day AI will be capable of replacing human relationships with their nuances and tactility? Whatever happens we’ll always need physical places for contact, spaces where humans can connect; cafes, courtyards and parks touched by the musings of great thinkers.

Take Piccadilly Circus, where historic architecture stands next to tech. LED screens flash brilliantly with lights and ads next to The Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain, which has called the spot home since 1892. But people flock to the fountain. It’s a place for celebration, dancing, a tourist hot spot and a meeting point for locals. Do we only accept the screens because they’re steeped in and surrounded by the history of the city?

Often when you ask people what they love about London they’re likely to choose the historic; Neal’s Yard at Covent Garden, Portobello Road in Notting Hill, or the Truman Brewery on Brick Lane – these places are traditional in their urban form, holding heritage and history. And that familiarity is something that holds strong in people’s psyche. Part of planning for the future is about understanding human desires and making room for them to co-exist in new urban environments.

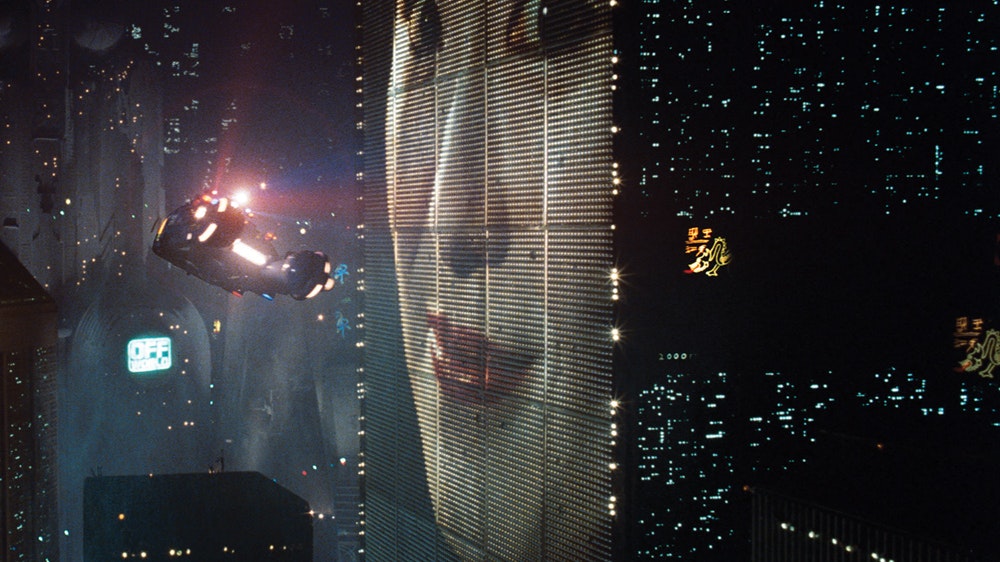

Even in the original Blade Runner, futuristic vehicles zoom through suspended channels and vast robotic trucks provide new means of transport, yet the humble bicycle continues to exist.

The future can sometimes seem like a frightening place as theory becomes fact. Computers recognise humans, we can soar tens of thousands of feet in the air, we keep in touch with people on the other side of the world, cars without drivers exist. And what’s next could be as far as our imagination can reach – trips to Mars, hologram housewives, teleportation. As they say, Rome wasn’t built in a day.