Lark Ascending

You might think that the route to fame and fortune lie in the twinkling lights of the City and the West End, but Lara Maiklem found both in the mud of the Thames. About a decade and a half ago, she walked down a rickety staircase leading down to the foreshore on the Isle of Dogs, near Limehouse, just across from Greenwich Peninsula. Maiklem had been raised on a countryside farm and loved the river. “It was a streak of wilderness in the middle of the city,” says the publishing professional.

However, up until that day around 2005, she hadn’t ventured directly on to the river’s banks. Taking the steps down to shore, she stood and examined this strange substrate of rock, sand, shingles and mud, which was also peppered with the castoffs from generation upon generation of fellow Londoners.

During that initial trip 15 years ago, Maiklem picked out a single clay-pipe stem from the riverbank, a common enough find, she admits today. “They’re everywhere,” she says. “I’ve found pipe stems from the tidal head of the river through to the estuary; sometimes you’re walking on them.”

Yet the artefact intrigued her, and she returned to the river a few days later, to pick out more things; she came back again and found more. “It turned into a bit of an obsession,” she says. “I moved to Greenwich in 2000, and I was right on the river, so I was going down on most low tides. It became more and more important for me.”

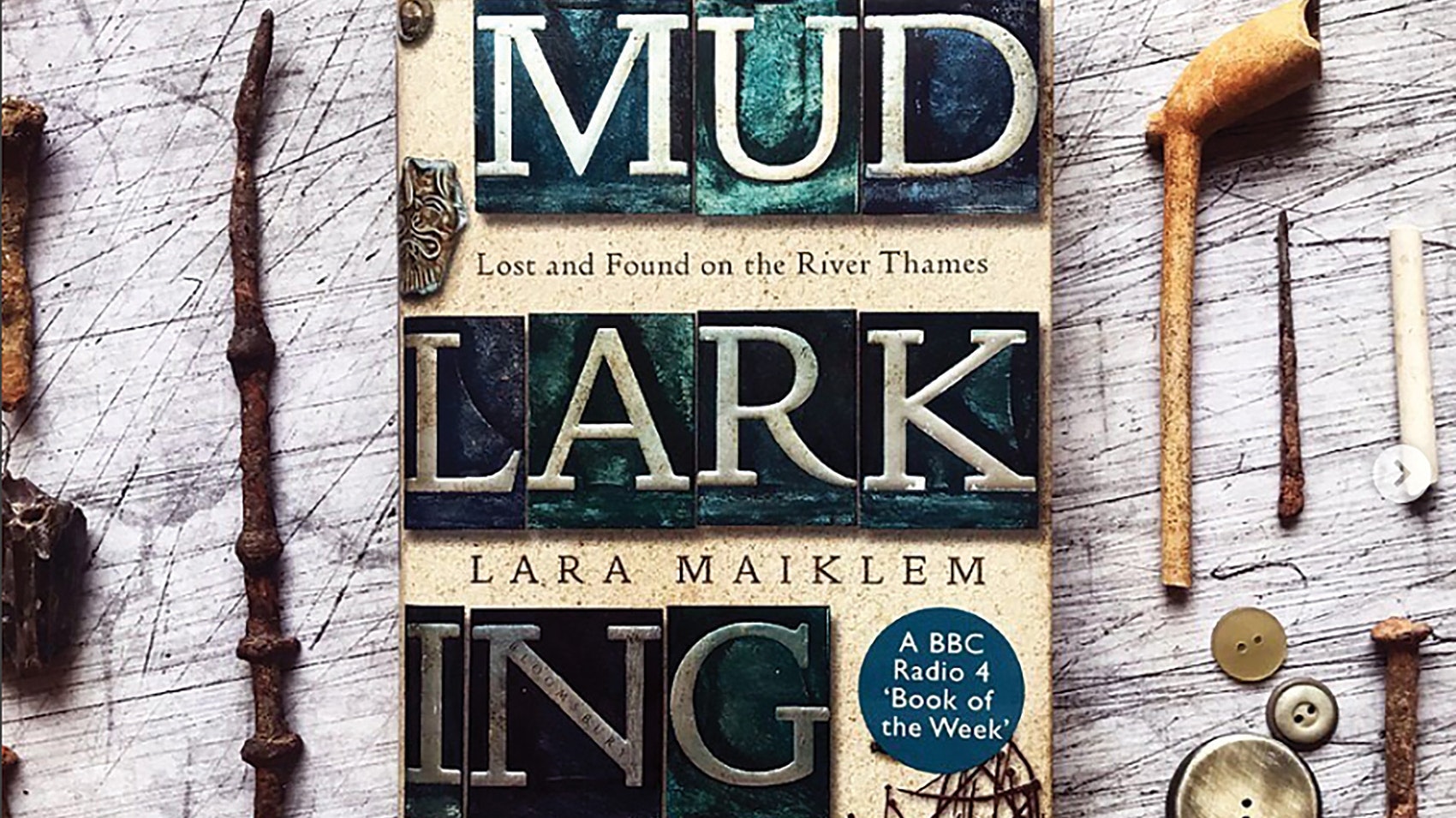

Maiklem came across others walking along the London’s riverbank, picking similar finds from the mud, and later read how the pursuit had been dubbed mudlarking, after an earlier term to describe London’s more desperate 18th- and 19th-century river scavengers. She started a Facebook group in 2012 and soon book professionals came knocking. Last year, Bloomsbury – best known for publishing Harry Potter – put out Maiklem’s book, Mudlarking, which has since become a Sunday Times bestseller.

The book’s success came as a surprise. “I think it’s been read by people who will never come down to the Thames themselves,” she says. “But it has brought mudlarking to a wider audience.” Maiklem says she has always been interested in history, “and a bit bored by history books,” she admits. “I grew up in a very old house, and it was that hands-on relationship with the past that interests me.”

Though her book is a hit, few of her finds are valuable, and Maiklem prefers to donate these discoveries to any museums that express an interest, rather than sell them online. The value for her lies in the way the riverbed links its visitors back to the earlier city.

“I moved to Greenwich in 2000, and I was right on the river, so I was going down on most low tides. It became more and more important to me.”

“It connects you with ordinary people from the past,” she says. “It’s the story of the city and how it's adapted and changed. You find barnacles from the Pacific, and coral from the West Indies, brought in by seafaring ships. Everything comes through there.”

She is careful to preserve this historical record; she holds a Thames foreshore permit issued by the Port of London Authority, enabling her to legally search and even dig up to 7.5cm into the shoreline of the tidal Thames, which stretches from Teddington Lock in the west, to the Thames Barrier in the east. “You must have one of these,” she says. “You can’t search without one.”

Maiklem also reports all her significant finds to the Portable Antiquities Scheme, which records and oversees archeologically significant finds in the UK. Some of the things she has turned up are very old and fashioned from precious metal, and so qualified as “treasure”. She donated a gold lace Tudor aglet – a metal tip for laces – to the Museum of London, but says it’s the only object of hers that official bodies have expressed much interest in. “They’ve got warehouses full of this sort of stuff.”

In fact, the things she really likes aren't especially prized on the open market. “My favourite find is a complete Tudor shoe,” she says. “I pulled it out of the mud just as it had been when it went in, 500 years previously.”

Maiklem could even make out the imprint of the wearer’s toes and heel. It was such a small shoe that she assumes it must have belonged to a young boy. “How did it get lost?” she still wonders. “Was he running quickly across the mud, and it came off on his foot? Was he climbing into a boat and it dropped off? Was someone bullying him and threw it into the river? And how much trouble did he get into when he turned up at home with one shoe?”

She has also come across more adult finds, such as a scabbard belonging to a Roman auxiliary soldier – “only the second complete one that’s been found in the country” – and an 18th-century token for Lambeth Wells, one of London’s old pleasure gardens (“That was really nice”).

She’s also picked up less-welcome finds, such as the odd tummy bug, and is careful to wear latex gloves when she mudlarks and wash her hands after returning from the riverbank. “The Thames is an urban river,” cautions. “It’s got nasties going in it.”

She also advises mudlarkers to take a mobile phone, check tide times – the lowest ones come during the equinox – keep an eye on exit routes, which can disappear as the tide rises, and watch out for very deep mud. “You can get stuck in it,” she warns. Still, she’s also happy to share her passion with other like-minded Londoners: “I can’t imagine any better way of experiencing history.” In digging into that history, she’s brightened her own future.

Mudlarking by Lara Maiklem, is out now, published by Bloomsbury Publishing.