Snap Judgements

Half a century after HMT Empire Windrush’s arrival, Greenwich Peninsula’s NOW Gallery stages a photographic exhibition looking back at black and Asian heritage in England.

Photographs probably weren’t the first thing on the minds of the passengers of the HMT Empire Windrush when it reached Tilbury docks in Essex, on the Thames, a few miles north-east of Greenwich Peninsula, on 21 June 1948. Yet its 1,027 disembarking people, most of whom were from the Caribbean, would have known that they looked different.

They weren’t the first black immigrants into Britain. Yet their arrival did “serve as an important hinge between the large numbers of black men and women already represented in many walks of British social life before the war,” explains the Jamaican-born academic Stuart Hall, “and the later arrival (in significantly enlarged numbers) of black people as an identifiable group to live, work and settle on a permanent basis.”

As subjects of the British empire, those living in Jamaica, as in Britain’s other colonies, had longstanding rights to settle in Britain, yet the British Nationality Act 1948 formalised this, leading to these larger, more identifiable groups. In most cases, they came for work, as Britain was short of labour in a number of key areas at that time, and took work offered by the newly formed National Health Service, as well as jobs in public transport and the postal service. Many tried hard to fit in, while understanding that they stood out.

This larger, heightened racial profile also coincided with new ways of seeing and being seen. Though commercial, amateur photography also predates 1948 by a good few decades, that year did see two important developments. Kodak introduced its first fully automatic photographic processing machine; using a continuous supply of paper, rather than individual squares, the contraption could produce 2,400 finished snapshots an hour. That same year, Polaroid brought out its first commercial instant camera.

This shift in both race and photography is masterfully captured in Human Stories: Another England, an exhibition of historical and contemporary trends in black and Asian heritage in England.

“They served as an important hinge between the large numbers of black men and women already represented in many walks of British social life before the war.”

Hosted in partnership with Historic England, and free to view from 10 October–11 November at NOW Gallery on Greenwich Peninsula, the show spans a century (1918-2018). The dates are in keeping with Historic England’s wider project, Another England: Mapping 100 Years of Our Black and Asian History, which is an attempt to deepen our understanding of race in this country by crowdsourcing photographs and reminiscences from the British public.

Yet Kaia Charles, who has co-curated the exhibition at NOW Gallery with Historic England's Tamsin Silvey, says 1948 is equally as important, since the show tries to both follow the historical record, and, at points, question what we think we know.

“The provocation ‘Another England’ signifies stories and images under-represented in England’s collective history,” says Charles. “While celebrating multiculturalism, we aspire to provoke open and honest dialogue about the portrayal of black and Asian heritage in this country over the last century.”

The show features Asian immigrants, many of whom arrived around the same time as Windrush, following the partition of India in 1947. There are also sensitive pictures of Liverpool’s longstanding Chinese community taken by Martin Parr, a photographer many of us might know from his less flattering shots of sunbathers on the beaches of Britain and elsewhere.

“While celebrating multiculturalism, we aspire to provoke open and honest dialogue about the portrayal of black and asian heritage in this country over the last century”

Parr is among the more famous contributors to the show. Alongside images from his agency, Magnum Photos, there are shots from Autograph – the Association of Black Photographers, and from Historic England’s own archive.

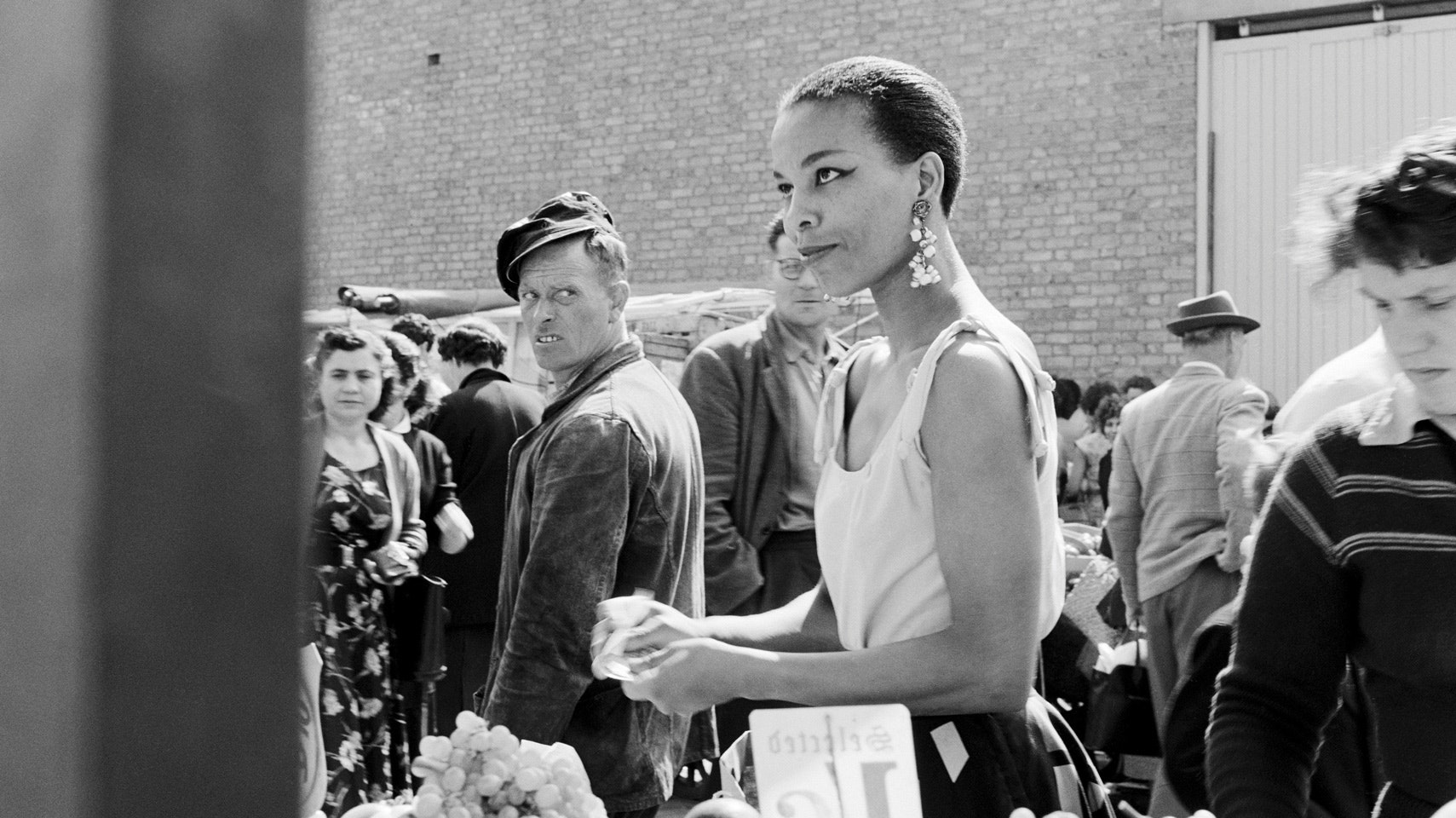

The pictures often confirm what we already know: that black and Asian people’s lives in Britain weren’t trouble-free. You only have to glance through the pictures on show to register the hostility on the faces of some white Britons, and the sharp suits and hats of the overseas arrivals suggest a kind of premium being placed on a sharp public appearance.

Even the medium wasn’t without in-built biases. Some have argued that the early colour film tended to favour pigment ranges better suited to capturing Caucasian faces, to the detriment of black portraiture.

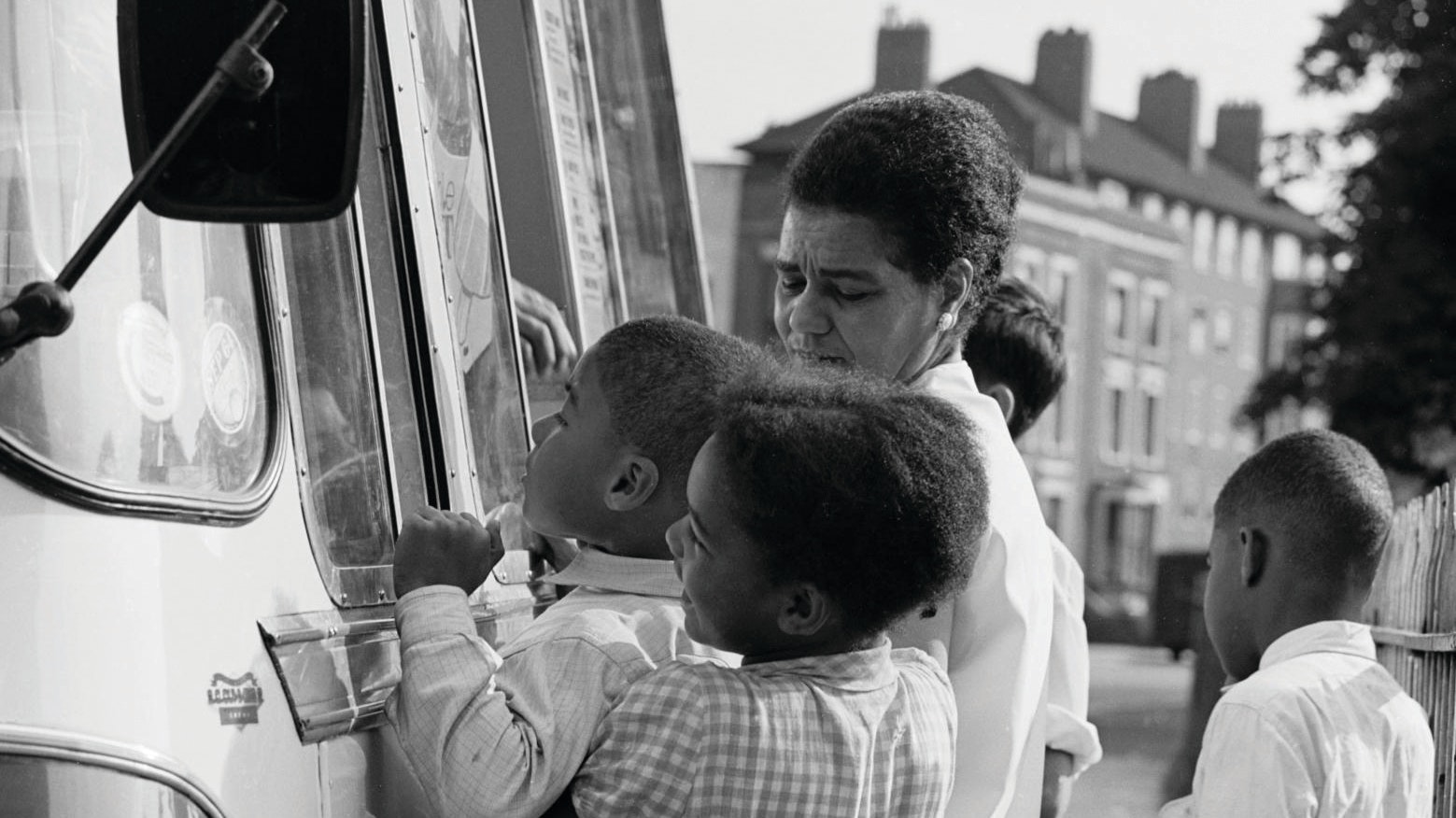

Yet the pictures also show happiness, empowerment – particularly in the case of Autograph’s contributions – and even just the humdrum, pleasantly boring aspects of living a decent life: the everyday activities of going to church, going shopping, or picking out a lolly from the ice-cream van’s selection board.

The few white faces in these pictures – often in the background – also tell their own story, too. Take the man in the cap, looking back at the young woman buying fruit from a market stall in north London. Perhaps he doesn’t know he’s being photographed; it certainly doesn’t look as if he feels the need to hide his sneer. She, on the other hand, is completely composed and civil, as if unaffected by both the camera and the man’s gaze. You don’t see such simple, bare-faced racism in England so much anymore, though you do see women like her. Looking back at this picture, it is him we consign to history and her we welcome forward.

Human Stories: Another England is at NOW Gallery from 10 October-11 November. nowgallery.co.uk