Feeling Good

Let’s set the scene; we’re descending some narrow stairs into a small underground room where the lights are turned down low and the air is thick with smoke and the smell of cologne. The low drone of a shruti box reverberates from every wall. Up on stage, an immaculately-put-together dandy walks their hands effortlessly across a double bass, while behind them a drummer in sunglasses teases out an easy groove on their ride cymbal. Then a harp comes in. And finally an alto sax begins its solo. This place sounds good. This place smells good. This place feels good.

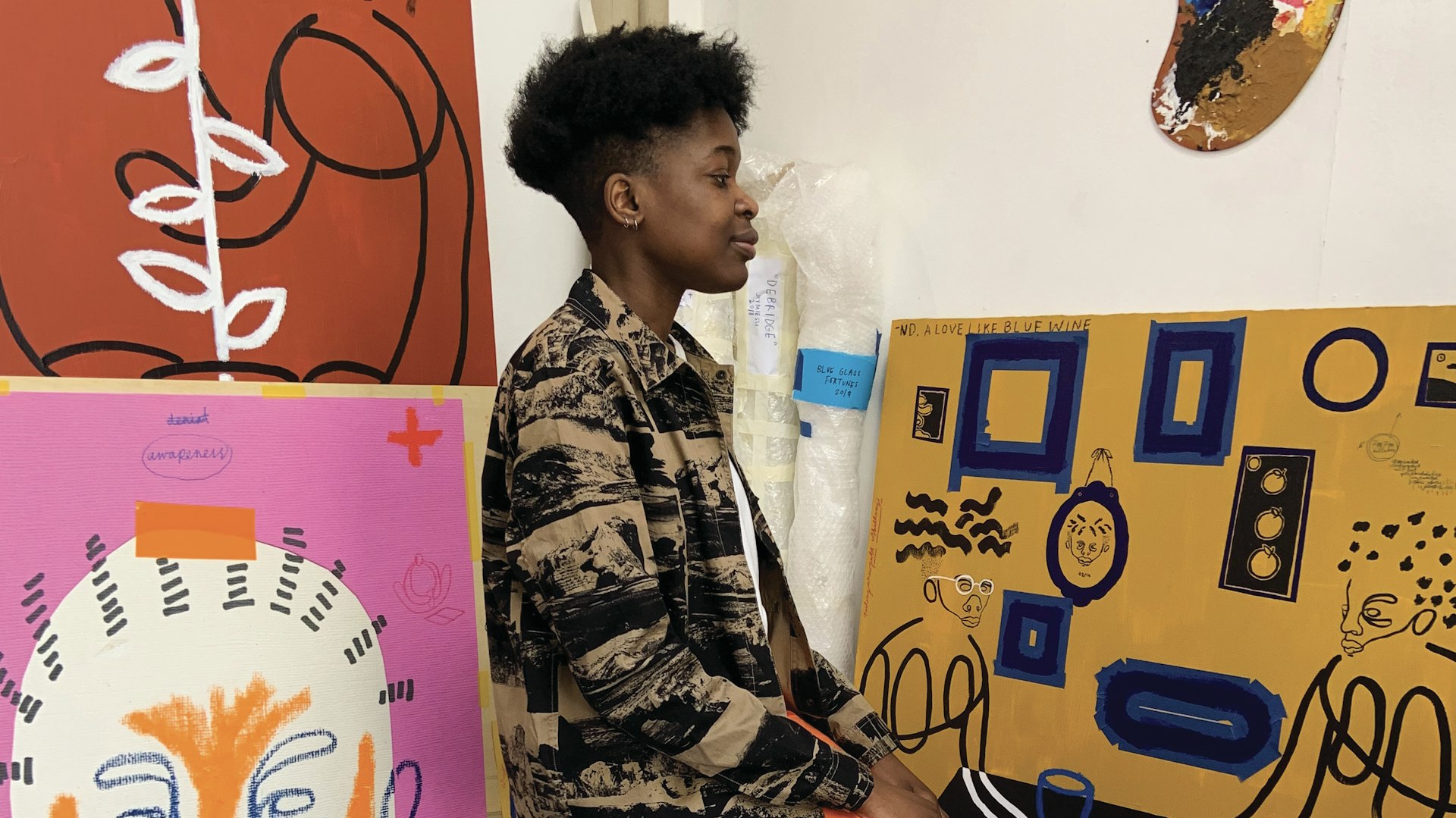

This place doesn’t actually exist, but the artist Joy Yamusangie has spent the last few months imagining it in their studio. They've used acrylic, pastels, oil bars, pens, pencils, elaborately stitched fabric samples and a heavy diet of mid-century and modern jazz to conjure a club with an atmosphere that feels freeing, life-affirming, evoking, says the artist, a sense of "gender euphoria and joy". And now they're offering it up to you as a playground.

Even though we’ve all been living under a rock for the last couple of years, there’s still a good chance you’ve come across Joy’s work before, either through their numerous collaborations with Gucci, their book cover for Penguin, their custom pairs of Nike sneakers, as part of It’s Nice That’s ‘Ones To Watch 2020’, as one of the contributors to Polly Nor and Ione Gamble’s Creativity4Change project, or as a winner of Best New Director and Best Fashion Film at 2021’s Fashion Film Festival, Milano.

That last accolade was for Wata, a film co-directed with the photographer Ronan Mckenzie, with whom Joy has been friends for many years. Wata explores the myth of Mami Wata, or La Sirene, a spirit venerated in west and central African mythology and across the African diaspora. The idea for the film came about when Joy and Ronan discovered that both their Congolese and Caribbean families respectively had stories to tell of Mami Wata.

So they set about creating their own myth, one that chronicles the journey of music from Africa to London, when Mami Wata meets a mysterious character known only as ‘The Musician’.

The resulting film is an arresting piece of cinema; hauntingly surreal, both sonically and visually rich. The original score features music by Birame Seck, Boofti, Melo-Zed and Roxanne Tataei and moves from dissonant vocals to blissful acoustic guitar strumming, electronic white noise and on to pizzicato disco-funk. This soundtrack forms the backdrop for effortlessly choreographed scenes danced by a cast clad head-to-toe in Gucci in rooms consecutively saturated with blue and brown hues. If this all sounds abstract, that’s because it is — it’s a fashion film after all — but the effect on the viewer is profound. It’s hard to think of a fashion film in recent years that has still been rewarding after multiple viewings.

Joy’s had a busier couple of years than most, and with good reason. Their paintings, sculptures, films and mixed media works are immediately alluring; bursting with movement and colour. But beneath that bright surface are rich depths in which to be immersed. Universal themes of memory and ritual and the familial and cultural practices that shape who we are mingle with subject matter that is deeply personal; explorations of gender identity, self-acceptance, mixed British Congolese heritage and the shared mythology of the wider African diaspora. “My work is often so autobiographical I don’t think I’ll ever fully get away from the intimacy,” says Joy.

Which is good for us, the viewer. It’s the intimacy that makes the work so compelling. Many of Joy’s works include snippets of diary entries woven into the painting, or placed above a scene like the words of an omnipresent comic book narrator. At times they are questioning and uncertain: “Do you know who you see?” At other times they are powerfully defiant: “On view I never grew used to daytime stares. but still I refused to change. Staring back, with eyes wide black, the day is mine too. Riding through to sunset + death drops.”

Some of these earlier works refer to experiences Joy had long prior to their professional career. Studying at art college in the south east of England, the new experience of artistic and personal freedom was tainted by bigotry in a parochial city, they say.

“Though it gave me access to things that I didn’t have before — screen printing rooms, letterpress machines and the space to work — my experience was clouded by the racism and discrimination I faced walking down the street, in class and even in the club. This imagination of a fictional club of acceptance has definitely stemmed from the lack of it in those formative years.”

The idea of the club came from reading the book Trumpet by Jackie Kay, which was in turn inspired by the real-life story of pianist and saxophonist Billy Tipton, who was posthumously discovered to be trans. Tipton’s life has proved fertile material for a number of other artists, inspiring an opera, Billy, a play, Stevie Wants to Play the Blues, and a jazz musical, The Slow Drag. It was also featured in a theatrical revue, The Opposite Sex Is Neither, by Kate Bornstein, a trans playwrite, performance artist and gender theorist. This is the first time that Tipton’s story has inspired its own club, though, let alone one with such feel-good vibes and chic clientele.

The other key inspiration behind Joy’s new paintings are Les Sapes, Congolese dandies from Kinshasa and Brazzaville renowned for their reverence for exquisite tailoring. “Their approach to fashion and fearlessness with colour and print I find really cool,” says Joy. “Les Sapueses in particular challenge traditional gender norms through the way they dress. I could see a lot of myself in them in some ways.

“What I also like about Sapologie is the respect for colour. Different colours have different meanings, so you dress yourself in colours that express how you feel. It’s not that different from what painters do with their work.” With this in mind, the club’s palette is limited to red, yellow and black, although there is one character dressed in a green suit so chic that the bouncers must have decided to let them in regardless.

As for the soundtrack, jazz is a form that Joy feels has a positive influence on their visual work. But this hasn’t always been the case. “It’s only over the last couple of years where I’ve come to appreciate it,” they say. “A lot of the songs that I love have this structure; rhythm, then improvisation and then rhythm again – and that’s it. It’s unexpected, sometimes breaking the rhythm and breaking rules. I love the fluidness and freeness of it. And that’s what I want to feel and what I want to do with my work.”

In spite of everything, Joy’s club feels strangely familiar. Strangers drink, smoke, dance, whisper secrets in each other’s ears and steal kisses in the shadows. Romance blossoms, fights erupt and people lose themselves to the music. What feels really different — perhaps uncomfortably so — is the level of positivity and support shown in the exchanges between the club’s patrons.

“...I want to feel good now,” says one character to the other in the show’s eponymous painting. “Yeah I hear you.” “Joy. We deserve that.” “We really do.”